Note: Check out the entire supplemental source code for this blog series.

Writing helpful and consistent commit messages is crucial for maintainability and collaboration. Luckily, there are some well established guidelines for us to follow.

Conventional Commits

Conventional Commits is a popular commit convention base on the conventions used by the angular team. The convention consists of five parts (type, scope, summary, body, and footer) arranged in the following format:

<type>[optional scope]: <summary>

[optional body]

[optional footer(s)]

Commit Type

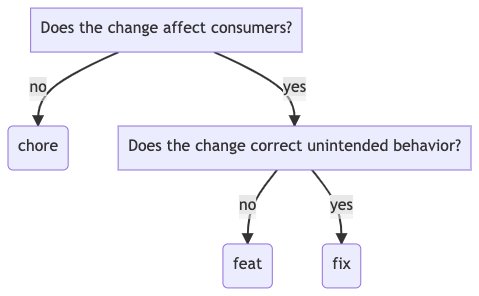

The type of a commit message is the most important part and is the first part of a commit message. You are free to use any types that you want, but you should try to stick to existing conventions and try to keep the list of possible types to as few as are needed. At a minimum, there should be three types: feat, fix, and chore. Having these three commits will let you distinguish between the three main types of code changes.

- feat: short for “feature” and can represent any new change in features or behavior that affects consumers.

- fix: essentially a bug fix, can represent any change to an unintended behavior that affects consumers.

- chore: can represent any change that does not affect consumers.

With just these three types, almost every code change can distinctly categorized following this flow chart:

The hardest part is probably in determining if the change corrects “unintended” behavior. If there’s a spelling mistake, then that’s a fix since the behavior was unintended. If you want to add a new word or sentence, then that’s a feat, but what if the change is a performance fix?

Ultimately, your team will have to decide how you want to classify these changes. The angular team, for example uses the perf type as its own performance type. Also, they decided that it was beneficial to further divide the chore type into several other types such as build, ci, docs, refactor, and test.

Atomic Commits

Commits should be as small as possible, but not any smaller.

A commit is atomic when it cannot be split into separate commits AND it still provides value on its own. Each commit should be valuable in and of itself and not just preparation for another commit that will (hopefully) come later.

If a change refactors some code, fixes a bug, and adds new behavior, it should be split into three separate commits so that each commit can fit squarely into just one commit type. This can lead to better historical documentation and is a way of more granularly stating intentions and reasons about why code changes. This will also allow you to ship smaller pull requests and can make both code reviews and reverts easier.

Let’s look at some examples:

If you need to create two separate classes to implement a feature, they should go in the same commit (assuming that one class without the other would not be valuable).

If implementing a feature requires that you split one class into two, then this could result in one or more commits depending on the circumstances. If splitting the class into two makes the library more maintainable or flexible (even if the new feature never comes), then the refactoring should be its own commit because it is valuable. However, if splitting the class does not make any sense if the new feature never comes, then the split should occur within the same commit as the feature.

Often times, when implementing a feature, I may find myself half way through implementation when I decide to refactor existing code or fix some existing bugs. My recommended approach is to pause and rewind (usually by stashing my changes), perform any refactoring that could be relevant to the existing code, then fix any bugs, and then, only after these two steps are done, unstash my changes and continue working on the feature. I often repeat this process several times and at the end of my feature I will have a series of chore commits, followed by several fix commits, and then finally my one feature commit.

Commit Scope

The commit scope identifies the area of code the change affects. This is going to be highly dependent based on the nature of your project. Some teams allow for dynamic scopes that can be made up on the fly, but I would recommend to keep the scopes static and to keep the number of scopes as small as possible. Unlike the commit type, the commit scope is optional for the times when your changes affect multiple scopes or just don’t fit cleanly into any one scope.

As an example, the angular repository consists of several npm packages and there is one scope for each npm pacakge.

Commit Summary

Sometimes referred to as the commit subject or header, this is a short summary of the change. Many teams enforce a character limit on the summary. The most frequent limit I’ve seen has been 50 or 100 characters. Condensing your code change down to just 50 characters can be challenging, but it’s usually doable with high-level thinking and some practice.

A common convention is to write your summary in lowercase and write it in the imperative tense such as to complete the sentence “Applying this commit will…”.

Commit Body

This is a more detailed description that can detail what was changed and why it was changed. Some teams require a body, some make it optional, and others forbid a body and instead leave these kind of notes elsewhere such as in a GitHub pull request. Your choice is really going to depend on your team’s tooling and workflow.

Commit Footer

The commit footer has several different uses. Some of the most common I’ve seen are:

- to use the

BREAKING CHANGE:key phrase to denote and list breaking changes - to reference issues that are affected and/or changed by this commit

- to include a git signature, such as

Signed-off-by: John Smith <john@smith.com>

Your team might decide to require any number of these or it might decide to omit the footer entirely.

Summary

In the end, the important thing is to get the team together and decide on how each of these five aspects of git commits will be used. My recommendation is to start with as few elements as possible and only add elements as they prove useful. I was on a team that did really well using only three commit types and a 70 character summary without ever using scopes, body, or footer. Try to use a convention that’s simple, restrictive and consistent.

When doing code reviews, treat commit messages as you would any other part of the code and review and provide feedback for each message. Once you’ve decided on a convention, make sure to document it, or, better yet, enforce your commit convention.